Marcel Van

396 pp. Gracewing Publishing 2006

Last week, I finished reading the stirring Autobiography of Marcel Van. Autobiography was the first hard copy book I’d ordered in possibly years, and it was a delight to be able to curl up with a blanket, cup of coffee, and the pleasant weight of a paperback once again. I was immediately intrigued by Van when I first learned of him: Born in Ngam Giáo, Bac Ninh in Vietnam in 1928, he is usually highlighted for his inspiring dialogues with St. Thérèse of Lisieux, which began when he was 14. But although these conversations are remarkable, there is so much more to Van than simply what one can learn about St. Thérèse through his experiences. After discovering the details of his life, I was both amazed and affected by his guileless sincerity, and the maturity with which he accepted and interpreted suffering. So much happened to Van at the hands of the Church, and yet he never ascribed his ordeals to the character of God, always looking to him instead for consolation. As I was reading through his narrative, Van felt instantly familiar and accessible, almost like a comforting fraternal presence accompanying the reader through the book. Though he frequently describes himself as small and fragile, the self-styled "little brother" of St. Thérèse, many people who are familiar with Van affectionately refer to him their "big brother" in heaven.

Once I learned of Van’s story, I read as far as I could into the Google Books preview, and when I could no longer piece together the narrative from every other page, went searching for the ebook. Unfortunately, it seems that Van’s incredible story is not as well-known as it should be. I ended up purchasing a hard copy from Amazon, tracking its every move until it arrived in my cold little Anchorage mailbox, and finished it about three days after it was delivered. I couldn’t help feeling a little sad when it I reached the end, as I was left wanting to know Van better. Happily, there are two other volumes of his writings and correspondences, which I definitely plan to read soon.

|

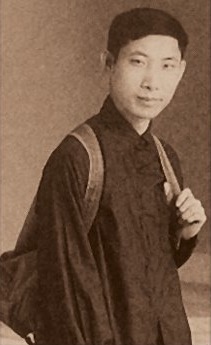

Van's photo from his certificate of primary studies. |

In spite of his anxieties, Van remained determined to pursue his vocation. His parents agreed to send him to the rectory of Huu-Bang when he was seven so he could begin his studies. But what should have been an edifying time of growth and development proved hellish for Van. Praised openly by the parish priest for his commitment to the priesthood and exemplary lifestyle, the other boys, and especially one older catechist named Vinh, began to demonstrate their jealousy. Vinh in particular severely beat Van on a daily basis, restricted his food, blocked him from receiving communion or saying the rosary, and attempted to rape him more than once. All in the name of instructing Van in what he called "the perfect life". Maybe worst of all, the teasing of the other boys caused Van to lose confidence in his relationship with God. "One thing tortured the soul of [Jesus’] little friend…”, Van writes of that time, “Victim as he was of a false opinion, worthy to be stamped upon, namely, that Jesus is not so accommodating as men." (73) But what is so awe-inspiring about Van is that even though he suffered intensely under the care of the Church, he always continued to turn to Jesus for encouragement. "In those days," he recalls, "all I knew was to offer myself to [Jesus], me, his little friend. I could only express my feelings towards him by a loving glance, filled with an ardent desire to be liberated from the yoke of this cruel idea... I would burst out sobbing, not understanding why I was not worthy, and Jesus was not happy. Jesus was the only one able to understand me at that time."

This was probably one of the things that most affected me in Van’s story. Since I was very young, I’ve struggled with the idea that God didn’t like or want me, or that any blessing I received from him was somehow obligatory. (I may explore this later, but the thought was first planted by my lack of “spiritual gifts” as a child, reinforced by certain reformed theologies as I grew up). I had a very happy upbringing and suffered nothing like the experiences Van underwent, so I was nothing short of amazed, and a little bewildered, at his steadfast faith, especially in his persistence through tangled feelings of devotion and unworthiness. His simple expression of sadness at the distance he felt between himself and his Creator, immediately followed by the confident assertion that the latter understood, was nothing short of profound. “The more I tried to unravel the problem,” he relates familiarly, “the more tangled it became, and the more painful was the wound to my heart… I knew only to put my confidence in God.” (63-64)

Unfortunately, things became worse for Van after severe floods and his father's gambling plummeted his family into utter poverty. No longer able to afford his necessities, Van’s parents relied entirely on the charity of the parish priest to support him. Now that Van was suddenly a burden, the priest became aloof and hostile. Van’s studies ceased entirely (the priest refused to grant him anything beyond a primary certificate), and he was forced to perform manual labor for the rectory while his abuses continued. The rectory for its part degenerated into drinking, gambling, and frequent visits from questionable girls, activities which Van was ceaselessly harassed for not enjoying. He attempted to return home several times, but was fiercely rejected by his family who could no longer afford to support him. Briefly, he even resorted to begging on the streets rather than continue in the environment at the parish.

Miraculously, after seven years at Huu-Bang, Van was accepted into the Dominican minor seminary at Lan-Song. It was incredibly joyous news for the fourteen-year-old, however after only a few months the seminary was forced to close due to bombing by the Japanese. Fortunately, he was able to continue his education at the rectory of St. Thérèse's parish in Qang Uyên, and it was here that he discovered the autobiography of St. Thérèse, The Story of a Soul. On first seeing her little book, Van was unimpressed: “I summarized her life in an amusing manner in these terms: ‘Since her birth until her last breath she had many ecstasies and performed a number of miracles; she fasted on bread and water, only taking one meal a day; she spent the night in prayer and gave herself the discipline until she bled. After her death her body exhaled a very pleasant fragrance and many extraordinary things happened on her tomb. Finally she was canonized by the Holy Church… etc.” (227) But only two pages into Thérèse's writing, Van found himself moved him to tears, for here was the "little way" to God that he had longed to find. "What moved me completely," he writes, "was this reasoning of St. Thérèse:"

'If God only humbled himself towards the most beautiful flowers, symbols of the holy doctors, his love would not be absolute love, since the characteristic of love is to humble oneself to the extreme limit.' Then, taking the sun as an example, she writes: 'As the sun shines at the same time on the cedar and the little flower, in the same way the divine Star especially lights up all souls, big or small.' Oh what reasoning, so deep in its simplicity! In reading these words I was able to understand, a little, the immensity of God's heart, which goes beyond all created limits; that is to say, it is infinite... I understood that God is love and that Love adapts itself to all forms of love. Consequently, I can become holy by means of all my little actions: a smile, a word, a look, provided that all are motivated by love. What happiness! Thérèse is a saint who corresponds totally to the idea I had in mind of holiness. From now onwards, sanctity will no longer frighten me.

Having finally found the saint he longed for, Van asked Mary to make Thérèse his spiritual sister. A short time later, he heard Thérèse speak to him for the first time, and indeed it was in the gentle, even teasing voice of an older sibling: "Van, Van, my dear little brother!" During the course of their conversations, which would continue throughout his life, Thérèse introduced Van to the infinite love and fatherhood of God. One theme of their dialogues affected me in particular, namely the emphasis which Thérèse placed on speaking familiarly with God. Van relates this guidance from her:

'[W]hen you speak to the good God, do so quite naturally as if you were talking to those around you. You can speak to him of anything you wish: of your game of marbles, of climbing the mountain, of the teasing of your friends, and if you become angry with anyone, tell it also to the good God in all honesty. God takes pleasure in listening to you; in fact he thirsts to hear these little stories which people are too sparing with him. They can spend hours telling these amusing stories to their friends but when it's a question of the good God who longs to hear such stories to the point of being able to shed tears, there is no one to tell him about them. Fron now on, little brother, don't be miserly with your stories to the good God. All right?' Thérèse laughed.

Though in my own religious education I was encouraged to pray often (and not just to ask for things, but also to express my gratitude), I had never been encouraged in quite this way. God may frequently be described as longing for “friendship” with us, but it’s quite an abstract idea when the same God is then immediately described as an omniscient, omnipotent, and omnipresent deity whose ultimate goal in everything is the glory of his own name. What would that friendship even look like? Through Thérèse’s instruction (though each of these traits may be true) we come to understand God as someone who is far more intimate with us, someone we should feel no hesitation in approaching with the details of our lives. Along with Van, we learn that God is someone with whom we can build an authentic friendship, in the true human sense of the word. It was a passage that had great impact on me.

During her life, Thérèse had been selected to go to the Carmelite convent in Hanoi, but her health ultimately prevented her. In her dialogues with Van, it seems, she was finally able to express her heart for Vietnam, and it is in fact one of the most striking things about their relationship that Van, a Vietnamese boy of 14, was so open to the teachings of a woman from his country’s colonial power. Van makes no secret of his feelings towards the French: “[T]he French colonialists, may they be thrown into hell to teach them what they are,” he seethes. “Their cruelty is diabolical and they consider the Vietnamese as a contemptible race only deserving to be crushed under their heels... If I had in my hands only one revolver I would, nevertheless, dare to raise the standard of rebellion to fight against the French, and even if I only killed one of them, that would suffice to make me happy.” (245) It is remarkable that in his rightful detest of the French colonial atrocities, he is somehow able to maintain the discernment to distinguish between colonialists and missionaries, the latter of whom he writes “are French, but dedicated totally to Vietnam; so much so that they could be called the fathers and teachers of the Vietnamese people.” Thérèse for her part, asks Van to pray for France. He assents (reluctantly), and begins to pray for the French daily. Even though as he describes it, “[E]ach time that I have to pray for France, I feel a malaise and I suffer as if I’ve placed a kiss on a branch covered with thorns.” (249) His cause for beatification would later be opened in the French diocese of Belley-Ars in 1997.

Sadly, even though Van was learning so much from his new sister, he encountered increasing difficulties at the rectory. The female tertiaries who served the the food were hostile towards the students, and severely underfed them to the point of starving them. When Van brought this to the attention of one of the fathers, however, he was scolded for being indulgent, even gluttonous. During the ensuing discussion Van held his ground, asserting, "'I cannot lack faith to such an extent that I allow myself to die of hunger in the presence of this infinite power who is God, my true Father. When I am hungry, I ask him for food. When I am thirsty, I ask him for drink. That is what God wishes me to do. If I did not act in this way it would seem that I was behaving towards him as a stranger." (272) When the father continued to interrogate him on self-denial, Van’s response reflected the teachings of his spiritual sister:

'For me, I can only reach holiness by conforming to the human condition fixed in advance by God… If, after having followed this line of conduct I fall ill, I will recognize that this is a special favor from God, a cross coming from his hand, and I will accept it willingly through love for him. A saint who would live in squalor to become ill, and once ill, would moan on his bed saying that he puts up with his illness with joy because it is the will of God: I would consider him as a strange saint and I would ask myself if he is really sure that God can rejoice to hear him attribute this sickness to his holy will.' (273)

It was also during his time at Hanoi that Van met the man who would become his spiritual director, Father Boucher. Father Boucher asked Van to commit the story of his life to writing, as well as the dialogues he had with Jesus, Thérèse, and others (these were published under the title Conversations). It is at this juncture that Van takes his leave of us, at least in his Autobiography. We learn from Father Boucher that after the division of Vietnam, while many Catholics were flooding south, Van volunteered to go to the North with a group of others in 1954, "so there will be someone who loves God in the middle of the communists." (353) While out shopping in 1955, he contradicted someone's claims about the government in South Vietnam and was arrested on trumped up charges. When he refused to change his story, he was sentenced to 15 years of hard labor in a re-education camp, where he passed away in 1959. He was 31 years old.

It is no surprise, however, that Van’s work continues. In a film produced by the Marcel Van Association, many people attest to Van's intimacy as a "big brother", teaching them through his writings and interceding on their behalf. His sister, a Redemptorist nun in Canada, remarks in the film that Van has the soul of an apostle, ardently pointing others towards Jesus. She summarizes his mission in the following way: “It is always about confidence. When there are times of discouragement, confidence! Jesus always keeps his word... Never abandon prayer, stay very close to Jesus. The more you accept your weaknesses, and the more you offer them to Jesus, this offering becomes a strength for other souls.’” It is precisely this message of confidence in God and accepting personal vulnerabilities, evident throughout the book, that most moved me, a message I will continue to keep close to my heart.

|

The last photo taken of Van (going shopping in Hanoi in the spring of 1955) |

I'll end with my favorite quote from the book, which summarizes the sincerity of Van’s commitment to God and to living his life in love despite his “littleness”:

I feel a little embarrassed and you, perhaps, cannot stop smiling on seeing the insignificant things that cause me suffering. In truth, you will have noticed that things that great souls would consider ordinary and of little importance are, for me, a heavy burden, and without divine grace I would not have been able to carry them. I know well that it must have been so, because my very small and imperfect soul easily becomes anxious and is unable to contain its emotion even before the smallest obstacle. This is why I wish to say with little Thérèse: 'Because I am very small I have only very little sacrifices to offer to the good God.' (348)

No comments:

Post a Comment